The Memory Problem- Why Your Agents Fail: Part 1

What happens when the knowledge that runs your company lives only in people's heads.

When a company decides to switch suppliers, someone usually has a reason. Maybe the current supplier raised prices. Maybe they had quality issues. Maybe there was a six-week delay that messed up a product launch. Whatever the reason, someone in the company knows it. The VP of Operations remembers the delay. The procurement manager knows about the price increase. The quality team has documentation of the defects.

Six months later, when the company is considering switching back, or switching to a similar supplier, that knowledge exists in fragments across multiple people’s heads. The CTO might remember there was some problem with the old supplier, but not the details. The new procurement manager wasn’t even at the company when it happened. The documentation exists somewhere, but it’s in desk notes, emails, meeting notes, teams / slack threads - nowhere anyone will actually look when making the next decision.

This is how companies work. Contextual knowledge lives in people’s heads. When you need to make a decision that requires that knowledge, you get those people (aka stakeholders) in a room. If they’ve left the company, the knowledge leaves with them. If they’re busy, the decision waits. If they remember wrong, you make a worse decision. Life finds a way :)

The reason companies evolved this way is that it used to be the only way. You couldn’t (or did not need to) store context. You could store facts. Things like, this supplier A costs this much, this ingredient X has these properties, but not the reasoning behind decisions. Even your data lakes and “Business Intelligence” dashboards that sit on top of them do not show reasoning intelligence behind decisions. So companies developed elaborate organizational structures to compensate. You have a procurement department that specializes in supplier decisions. You have a quality department that tracks issues. You have cross-functional teams that meet to share knowledge. The structure of the organization is literally a workaround for the inability to store decision context.

This worked fine when humans were making all the decisions. Humans are good at reconstructing context from fragments. You tell them there was some problem with the supplier, and they can ask questions, probe for details, triangulate from multiple sources. They can say “wasn’t there something about a delay?” and someone else will say “oh yeah, that was when we were trying to launch the protein shake and they couldn’t get us pea protein for six weeks.”

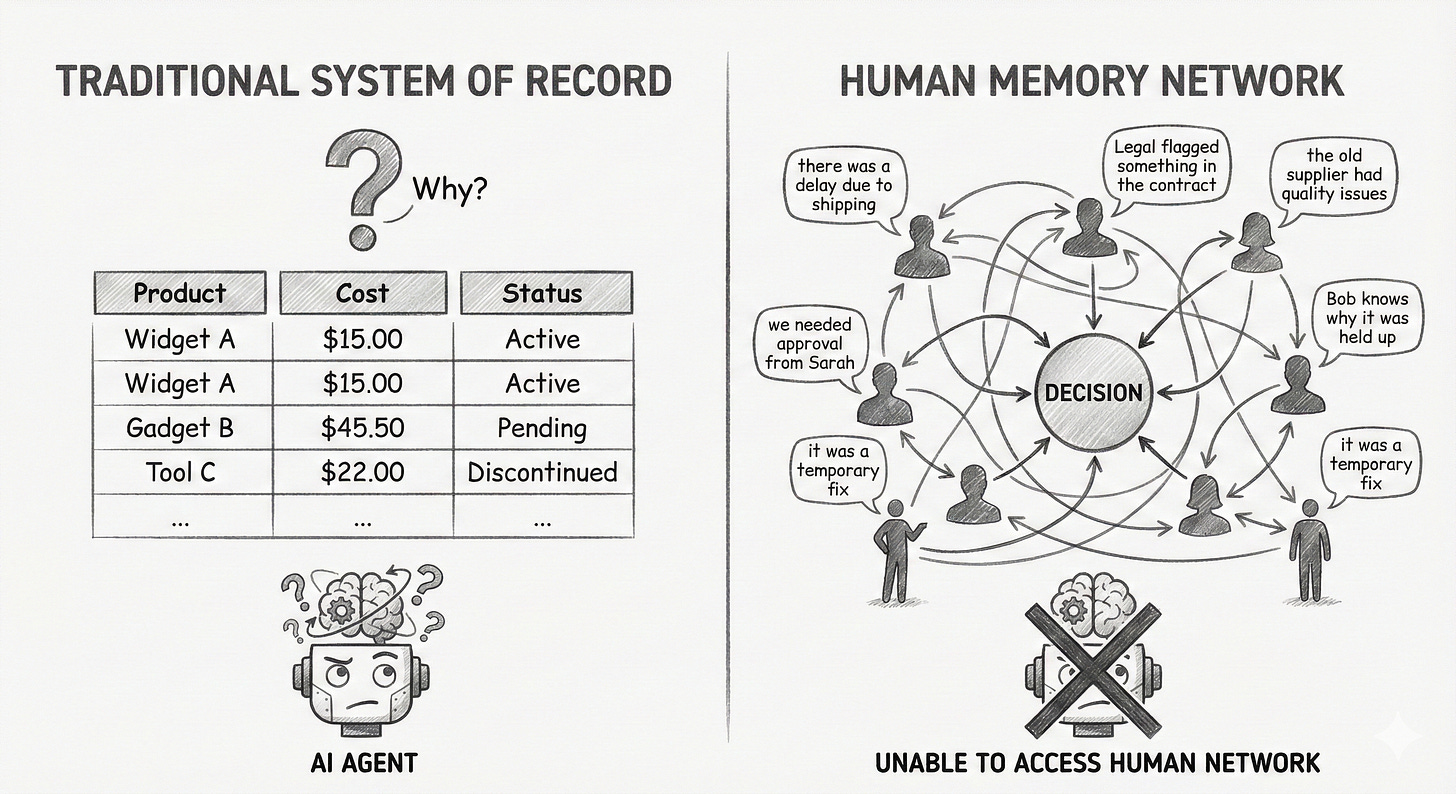

But now companies aspire to have AI agents to make these decisions. And if you have attempted this, you know Agents can’t do this well. They can’t reconstruct context from fragments scattered across multiple human brains. They can’t intuit that the real reason you switched suppliers wasn’t the official reason in the documentation. They can’t know that when Finance approved that margin exception, it was really because Legal had flagged something else that made the cheaper option impossible.

The agents fail, and companies conclude that AI isn’t ready for complex decisions. But the problem isn’t the AI. The problem is that the decision context was never in a form anything except humans could use.

What Gets Lost

Traditional enterprise systems are optimized for storing state. Product X costs $2.50. Supplier Y has a reliability rating of 0.78. These are facts. You can query them. You can update them. The systems are built around the assumption that knowing the current state is what matters.

But when you’re making decisions, what matters isn’t just the current state. It’s how you got there. Why does Product X cost $2.50? Because we selected pea protein instead of whey. Why did we select pea protein? Because whey had a supply chain issue in APAC. Who decided to override the 15% margin warning? Sarah from R&D, and Finance approved it because of strategic alignment with health trends.

None of this context exists in traditional systems. The database has the price. It doesn’t have why someone decided to accept that price. It has the supplier rating. It doesn’t have the story of what happened with that supplier that led to the rating.

The context lives in email threads, Slack messages, meeting notes, and most of all, in people’s memories. And for human decision-makers, this is normal. When Finance needs to approve another margin exception, they can call Sarah and ask what happened last time. Or the VP remembers and tells the story in a meeting.

But watch what happens when you try to automate this with AI. The agent has access to the database. It sees that pea protein costs 15% more than target margins. It sees that this was somehow approved anyway. It has no idea why. It can’t call Sarah. It can’t reconstruct the context from fragments. So it either blocks the decision (too conservative) or approves it without understanding the implications (too risky). This is also another reason why we end up designing with too many human in the loop steps around agents.

The Event Clock

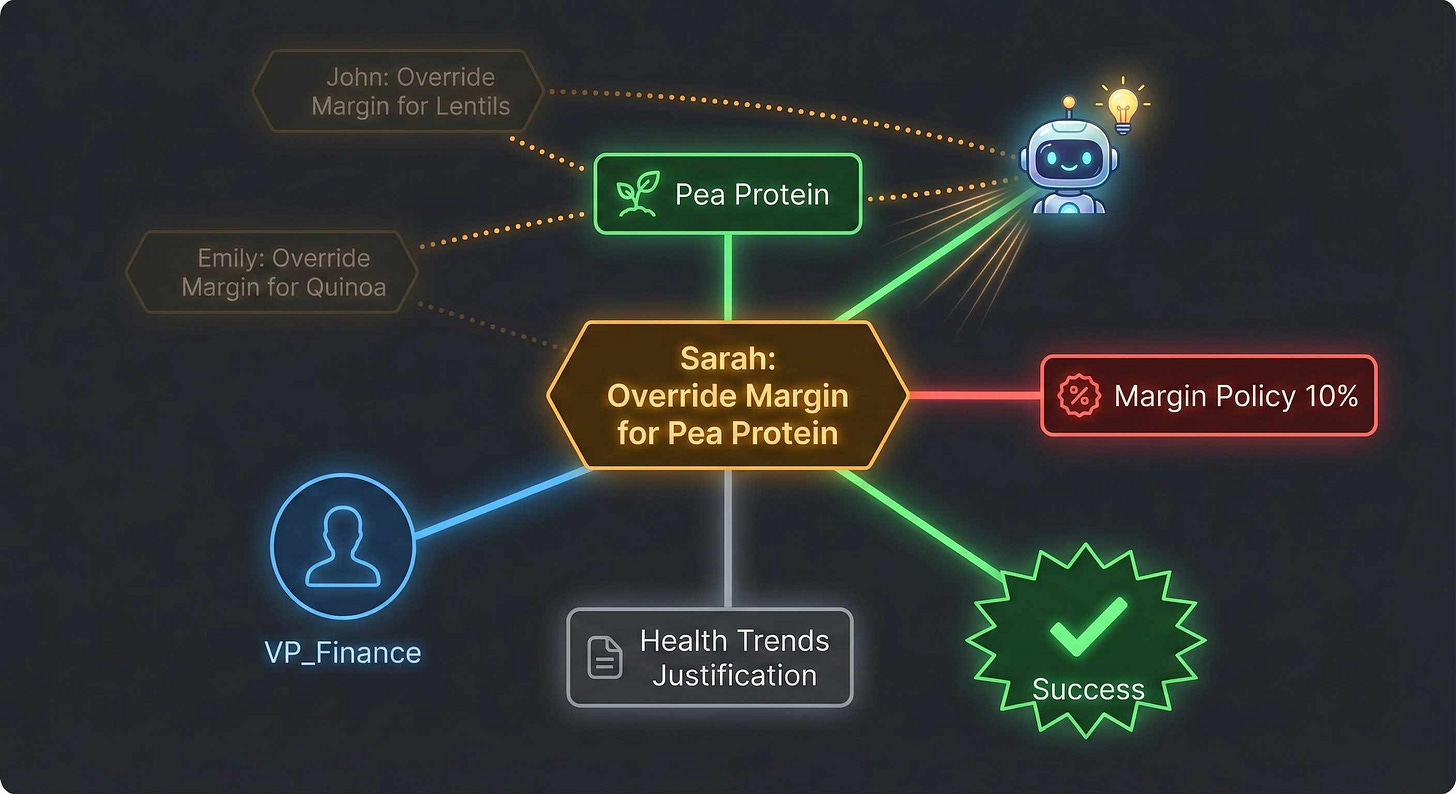

There’s a different way to store this information. Instead of recording state, you record events. Instead of “Product X costs $2.50,” you record “Sarah from R&D selected pea protein for Product X, overriding a 15% margin warning, with the justification that it aligns with strategic health trends, approved by VP_Finance.”

This looks like verbose logging. But the key insight is that you make these events first-class entities. You don’t just write them to a log file. You store them in a structure where you can query them, connect them, reason about them.

One way to visualize this is as a graph, but one without any explicit schema. Decisions, entities involved like ingredients, policies, departments, suppliers are nodes here. The edges capture relationships. This decision involved this ingredient. This ingredient is regulated by this policy. This outcome resulted from this decision.

Every time someone makes a decision, you capture not just what they decided, but why they decided it, what else they considered, what constraints they were working under, who was involved. The graph grows with each decision. And because you’re preserving context, you can answer questions that are impossible with traditional databases.

Has anyone approved a margin exception for protein ingredients before? The database can’t answer this. It can tell you Product X uses pea protein. It can tell you Product X somehow got approved. But it can’t tell you the margin exception was because of the protein, or who approved it, or why.

With a context graph, you traverse the structure. Find all decision nodes connected to margin exception nodes. Follow the edges to see what ingredients were involved. Look at the reasoning attached to those decisions. You discover that VP_Finance approved three similar exceptions in Q3, all for plant proteins, all justified by market penetration strategy. Over time as you collect this data, a better picture of your organization emerges.

This isn’t just better search. It’s a different kind of knowledge. You’re not retrieving facts. You’re retrieving the collective memory of how decisions actually got made.

Why This Matters Now

The timing of this matters because of agents. As long as only humans were making complex decisions, the current system worked. Humans could reconstruct context. They could navigate organizational politics. They could read between the lines.

But now, companies increasingly want agents to handle these decisions. Not just simple automation, but real decisions involving trade-offs, uncertainty, competing constraints. And agents can’t access the collective memory stored in human brains.

The natural response is to give agents access to more documents. Hook up RAG to the entire Slack history, all the emails, every meeting note. But this doesn’t work well. The information is unstructured and the relationships are implicit. You’re hoping the embedding model will somehow figure out that this Slack thread about supplier issues is related to that email about margin exceptions, and both are relevant to this decision about ingredient selection.

Context graphs make the relationships explicit and at the source. When Sarah decided to use pea protein, that decision got connected to the margin policy it violated, the supplier it depends on, the regulatory constraints it satisfies. The structure is already there. An agent doesn’t have to reconstruct it from unstructured text. It just traverses the graph.

This is why context graphs matter now in a way they didn’t five years ago. Five years ago, storing all this decision context would have seemed like over-engineering. We have people, policies and processes that take care of that.

Now the answer is: because you want agents to make these decisions, and we need to give agents the right context to take decisions. That context used to live in the human-memory system we’ve been using called the org structure.

If you’re building agentic systems now, most likely you are building systems that have human in the loop. You need to design to capture this decision intelligence as you build these systems. Don’t just give a binary option to the human in the loop to approve or reject. Collect rich data. Use the LLMs to ask follow up questions and collect the reasons. Tomorrow, that information captured will help you move to a more autonomous system.

The pea protein vs. whey example really nails the core problem—traditional databases store outcomes but not the reasoning chain that led there. Context graphs sound like a game-changer for agent decision-making, especially the idea of making relationships explicit at the source instead of hoping RAG can pieece together implicit connections from scattered docs. The human-in-the-loop design tip is solid too—collecting rich decision data now (not just approve/reject) sets you up for autonomy later. I wonder how you'd handle conflicting contexts though, like when different stakeholders remember differnt reasons for the same decision.