Context Graphs: The missing link for a truly Agentic Enterprise

A follow-up piece discussing how context graphs may be the missing element in enterprise decision intelligence and building a truly agentic enterprise.

Background

In my last blog post,

I talked about how 2025 started with big dreams of full agentic autonomy but quickly showed us the gaps. We saw wins in coding and with specialized agents using multi-agent setups like Microsoft’s AutoGen or Anthropic’s deep research systems. I also added that Market Forces will force walled gardens to open up and that companies deploying agents across functions won't tolerate silos. My sales agent needs to talk to your finance agent, even if they're from different vendors. However, there was something missing from my article. I did not cover what was fundamentally missing from the current architecture, beyond Integration and change management to overcome the challenges of building more autonomous agents. It struck me only when I read this brilliant piece by Jaya Gupta AI’s trillion-dollar opportunity: Context graphs.

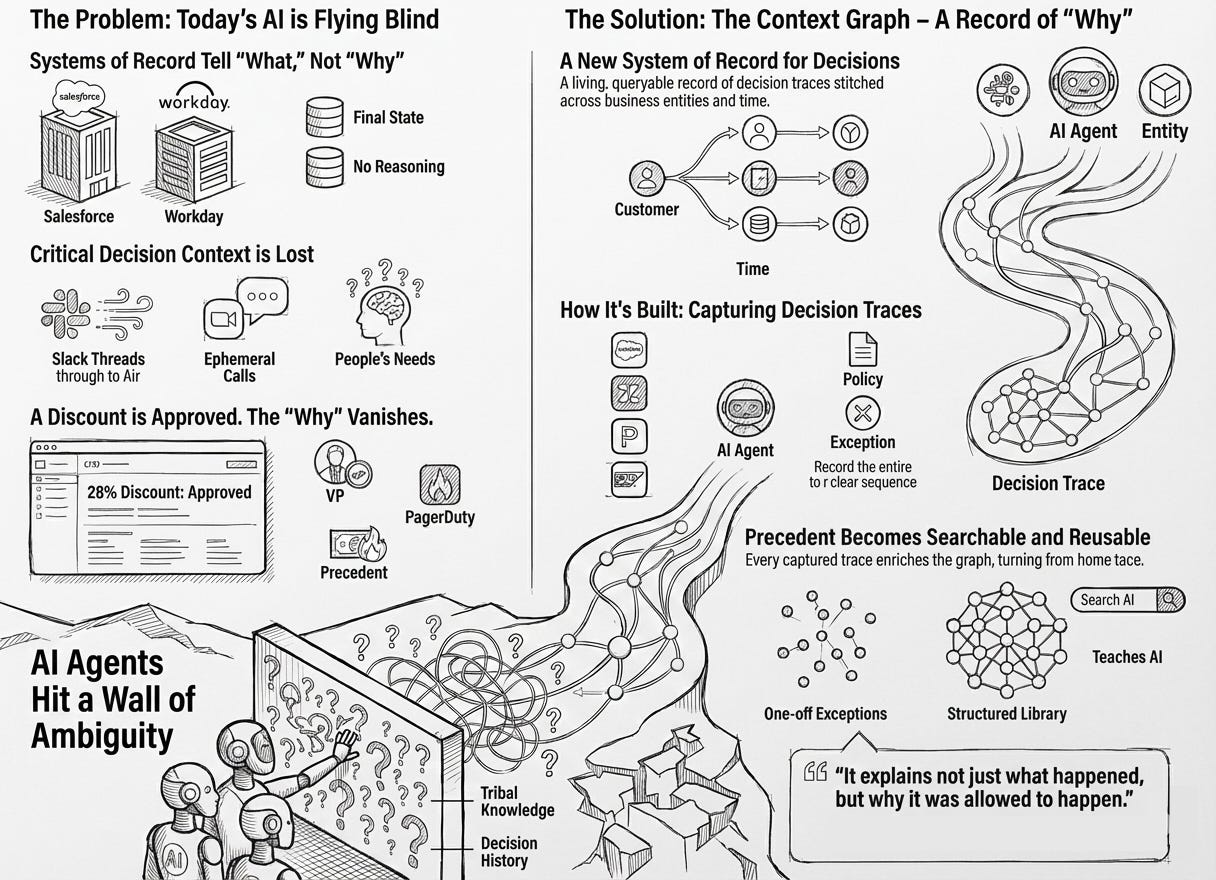

In 2025 a lot of people concluded that “agents don’t work.” What they usually meant was: they tried to give an LLM some tools and data, pointed it at a real business process, and watched it either do something scary or do nothing at all. Then they blamed the model. Most of the time the model wasn’t the main problem. The real failures were more systemic: systems didn’t line up, approvals were ad hoc, tribal knowledge was never captured. Adding more compute(inference time), larger models and tokens will not solve the problem and will only make the costs go up. Autonomous Agents failed the way a new employee fails when you drop them into a company with five CRMs, three definitions of “customer,” and a policy manual that exists mostly as vibes.

If you want agents that are autonomous but not insane, you need something that enterprises are surprisingly bad at building: memory. Not the model’s short-term context window, but institutional memory. The kind that lets you answer, quickly and precisely, “Have we seen this before, what did we do, who approved it, and did it work?”

Another way to look at this is codifying the company culture. In this context, I define a company’s culture as accumulation of behavior over time. Decisions and the provenance of these decisions shape culture and what employees actually do when faced with choices. This is never documented in an organization. There are no systems of record for capturing this. The decisions are captured but never the reasons for the same.

The missing piece is decision-memory middleware: a context graph.

Context graph is not knowledge graph or a RAG

When people hear “graph,” they think “knowledge graph,” which sounds like a big bucket of facts. Facts are nice, but facts don’t solve the problem agents have.

Agents don’t fail because they can’t find information. They fail because they are blinded from the why behind decisions.

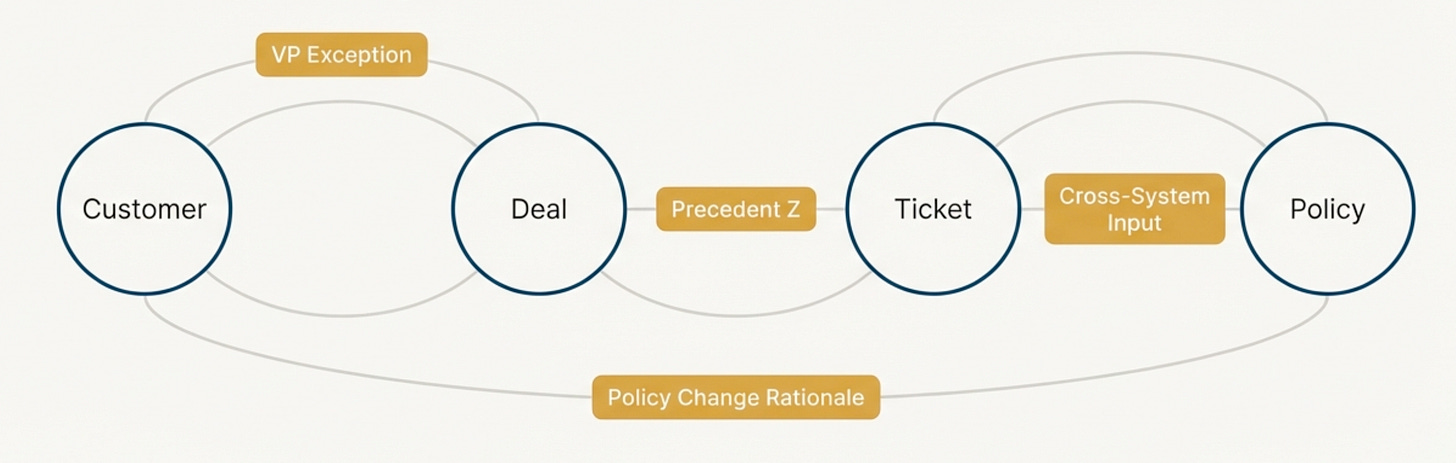

A context graph is a continuously updated graph of decisions and their provenance. It links the enterprise systems of records a decision touched (customer, deal, invoice, ticket), the policies it invoked, the tools it used, and the humans who approved or overrode it. It stores not just what happened, but why it was allowed to happen.

That last part is the part everyone regrets not having the first time an agent issues a refund, updates a contract field, or sends an email that sounds like it was written by a lawyer who hates you.

This is why “just add RAG” doesn’t fix it. Vector search can retrieve similar text. But similarity is not accountability. A pile of embeddings can’t tell you “this violated policy X but was approved by the team lead Jane with scope limited to invoices under $2,000, and later it caused chargebacks, so don’t do that again.”

Likewise, event logs aren’t enough. Logs tell you that something happened. They don’t tell you what it meant. They don’t give you reusable precedent.

And workflow engines, even good ones, mostly execute. They don’t accumulate judgment.

The goal is to make context into an asset, a first class citizen in the enterprise: something you reuse as precedent instead of re-deriving each time.

The shape of an institutional memory

To keep this from turning into “graph = magic,” you have to be explicit about what goes in it. Below is one of the many ways to do it.

The nodes are tangible things you already have:

Customer, Deal, Invoice, Ticket

Policy

Exception

Approval

AgentRun (versioned)

HumanDecision (override/escalation)

Tool (IssueRefund, UpdateInvoice, SendEmail)

Document (contract, email thread, SOP)

The edges are where it becomes useful, because edges encode semantics, not just links:

justified_bycited_documentviolates_policyapproved_byoverroderesulted_inused_toolsimilar_to

This is the causal chain an auditor wants, and it’s also the chain an agent needs if you want it to behave like a competent employee instead of a clever autocomplete engine.

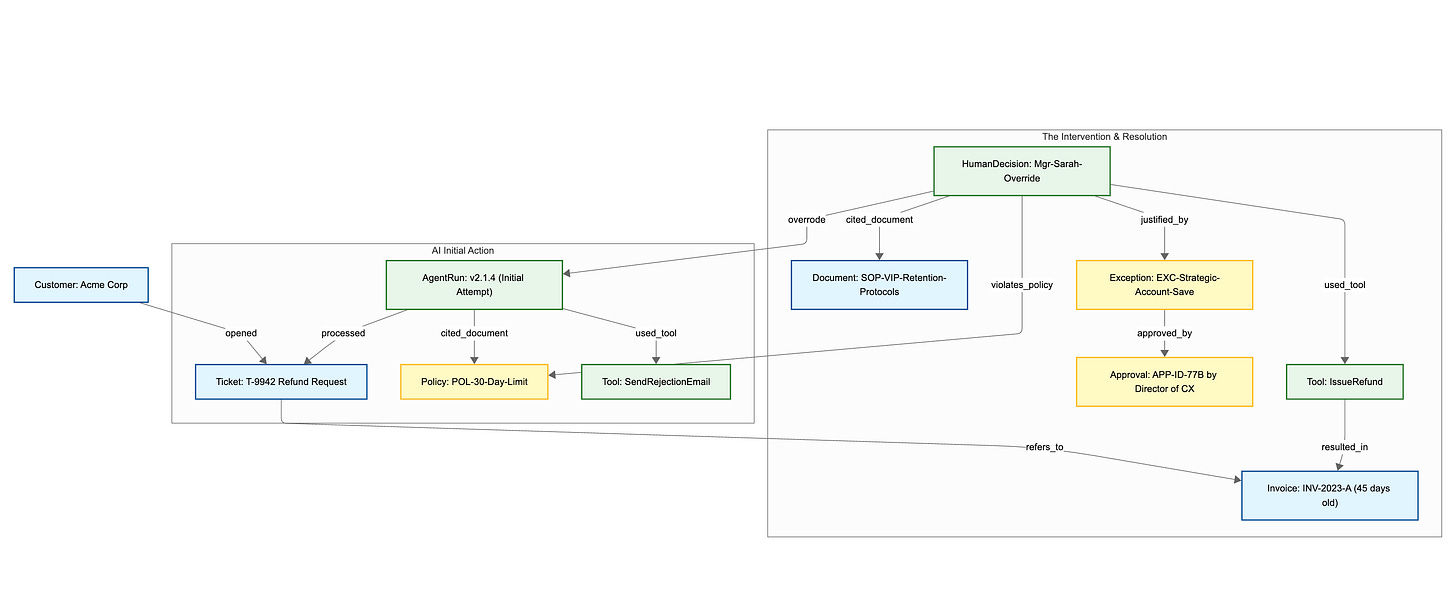

The Scenario: The “VIP Out-of-Policy” Refund

A high-value customer (Acme Corp) submits a ticket requesting a refund for an invoice that is 45 days old. The standard company policy is strictly “no refunds after 30 days.” An AI agent initially attempts to process the ticket and denies it based on policy. A human manager intervenes because Acme Corp is a strategic account threatening to churn due to a previous service outage. The manager overrides the AI and forces the refund through as a documented exception.

The Context Graph Visualization (Mermaid.js)

Here is a visualization of how these nodes and edges connect to form the institutional memory of that specific event.

What actually broke in 2025

If you look at the “agent failures” of 2025 mechanically, you see three recurring breakdowns.

1. Interoperability.

Agents couldn’t behave coherently because identity and semantics weren’t shared across systems. “Customer” in Salesforce wasn’t the same as “Customer” in NetSuite, and neither matched “Requester” in Zendesk. Without entity resolution, you can’t even do basic policy checks reliably, because you can’t be sure you’re talking about the same thing.

Tool-call standards help, but they’re not the real bottleneck. The bottleneck is standardizing what agents remember and emit.

2. Governance.

Governance sounds like committees, but in practice it’s exception handling. Nearly every real workflow devolves into: “Normally we do X, but in this case we did Y.” If you don’t capture exceptions as first-class objects with who approved them and under what scope, agents will either escalate everything (so you get no ROI) or they’ll handle edge cases incorrectly (so you lose trust).

3. Cost control.

Cost of intelligence dropped significantly in 2025. The token spikes weren’t just because models were expensive. They were expensive because agents kept re-deriving the same context. Multi-agent handoffs become costly recursion when there’s no shared, accessible memory. Each run rebuilds the rationale, constraints, and background like it’s the first day on the job. If you remember the move “50 First Dates”, you will be able to easily relate.

A context graph flips the default from recompute to retrieve-and-verify. You spend tokens on the deltas from precedent instead of on re-litigating the entire history of the account.

Bounded autonomy is a contract

People talk about “autonomy” like it’s a vibe. In practice you need a measurable rule.

Bounded autonomy can be as simple as:

An agent may act autonomously only when it can:

cite a relevant Policy node, and

cite at least one similar Precedent/Exception node, and

verify that no policy conflicts exceed thresholds.

Otherwise it escalates to human-in-the-loop review.

This changes the character of the whole system. Autonomy stops being a leap of faith and becomes something that expands gradually as novelty drops and overrides drop. You don’t argue about whether the agent is “ready.” You look at the override rate.

The human in the loop is important because every action taken by the human is net new context that goes into enriching the context graph. You form new connections and decision logic every time the human makes a call. This becomes the SOP for the agent going forward. The goal is to not have the human deal with a similar problem again and to have the agent take over.

The standard that matters

If you want this to work across vendors, models, and agent frameworks, the most important “standard” is not a tool protocol. It’s a trace schema: what every AgentRun emits into the context graph.

At minimum:

inputs + resolved entities

plan / proposed actions

tool calls + parameters

rationale + citations (documents, policies, precedents)

outcomes

human overrides and why

Once you have that, “agent behavior” becomes infrastructure. You can observe it, audit it, benchmark it, and reuse it.

How you build it without boiling the ocean

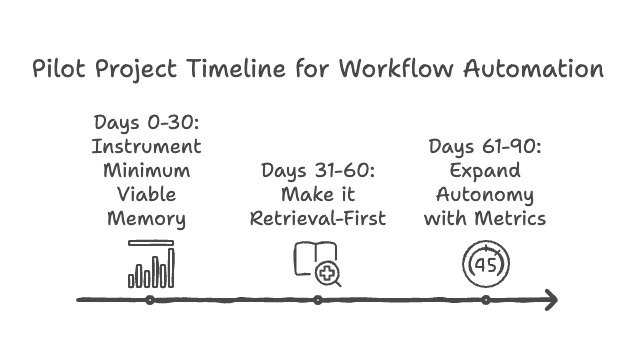

A 30–60–90 day pilot is enough, if you pick the right workflow: high-friction exception approvals, like invoice exceptions in sales/finance.

Days 0–30: instrument minimum viable memory. Capture inputs, plan, tool calls, rationale with citations, outcomes, overrides. Do identity mapping for the core entities.

Days 31–60: make it retrieval-first. Add similar_to search over past exceptions. Require “policy + precedent citation” before autonomous action. Introduce token budgets tied to graph hits. Cap max agent handoffs per case.

Days 61–90: expand autonomy with metrics: exception cycle time, override rate, novelty rate (no matching precedents), cost per resolved case. Only expand when override and novelty fall.

If this sounds like operations work, that’s because it is. The mistake in 2025 was thinking agents were mainly a prompting problem. Enterprises don’t run on prompts. They run on decisions.

Why the winners will look boring

By 2026 the winners won’t be the teams with the cleverest agent demos. They’ll be the ones who turned workflows into curated institutional memory: decisions with provenance, constraints, and outcomes, linked across silos.

That sounds unglamorous, which is usually a sign it’s real.

The secret is that autonomy isn’t something you bolt on at the end. It falls out naturally once you can remember what you did last time, prove why it was allowed, and notice when it didn’t work.